How to address the history of knowledge of nature from a materialist viewpoint, addressing how ideas, histories and complex narratives shape the materials they describe and are shaped by them? Who measures these material spaces, according to what metres, to what images of what is to be measured?

The Weight of a Living Thought: City as Cosmogram

El Caracol (the Snail). Photo by Gomez Rul in Sylvanus Griswold Morley, "Chichen Itza, An Ancient American Mecca," National Geographic (January 1925): 74.

The question “how heavy is a city?” at first seems to request an answer in standard units: an estimate of vast piles of construction materials. A moment’s thought, however, makes it a puzzle for Atlas and Archimedes. Just how far does the city proper stretch down, up, and out? Where could we place the lever or hang the balance to tally up the concrete, iron, glass, wood, stone; the humans, plants, and livestock; all the equipment and infrastructure; the goods, transport, storage, and production that bring a city to life? Like Osiris weighing the soul or an accountant’s last judgement, the thought exercise becomes a fable. It brings us to the paradoxes of origin myths, to Zen koans, to Borges’s stories. The city must be its own fulcrum: we have to reckon its weight while standing within it. As with mapping the universe, if we’re inside it, how do we grasp its limits and contours?1

Beyond its “objective” dimensions, a city is also the site of experiences, meanings, and images. Its weight in tons, kilowatts expended, CO2 emitted, GDP, or price per square meter can appear incommensurable with its experiential, symbolic, spiritual, and intellectual aspects—its weight in meaning. Even a holistic rendering of a city’s measurable dimensions, such as the “donut economics” model of economist Kate Raworth—which traces an upper limit for negative factors (toxic waste, crime) and a lower limit for social goods (education, health)—remains within discrete and technically-established measures.2 It perpetuates the “bifurcation” noted by Alfred North Whitehead between primary qualities and the secondary qualities of sense (color, smell, taste).3 The weight of a city should not trade stats for its specific feel and rhythm, for its dynamism and potentials.

Cosmograms—objects and images made to define and express the universe—elide the assumption of a split between things and thoughts, and shed light on the ways in which diverse conceptions of the order and constitution of reality are woven into objects and practices. They take many different forms, from creation stories or seasonal rites to magical sigils and popular science documentaries, to register the many different cosmologies and varied conceptions of the universe’s underpinnings. Instead of trying to capture cosmologies as “worldviews” or “cultures”—ambient sets of ideas, values, and beliefs floating in the ether, which are often only as solid, structured, coherent, and bounded as the ethnographies and philosophical analyses that summarize, or, more properly, invent them—studying cosmograms means looking at how people present that order to each other. Cosmograms set conceptions of the universe within active public life. As such, they gather things together, they get installed and activated, and they have short- and long-term impacts.4

Cites have been repeatedly presented as images of the cosmos, particularly those with sacred functions: Kyoto, Mecca, Ilé-Ifè, Jerusalem, Beijing, and Rome, just to name a few.5 The sacred idea of the city might be seen as a static image, a superimposed template that floats away from the actual one, making its concrete lifeways and constructions almost irrelevant. This is the city as the object of pilgrimage, of prayer and devotion, perhaps visited once in a lifetime, as with Mecca, or never, as with St. Augustine’s otherworldly City of God, eternally contrasting the cities of humans in which the faithful are exiles and pilgrims, longing and striving for a one-way ticket to their heavenly home. Yet cities materially frame and hold these invisible orders and powers. Like Sumer and Babylon, Paris was built around a central temple, a building for worship, Notre Dame. Cities like Tenochtitlan and Tulum were sacred sites for ritual and the performance of social and cosmic hierarchies.6 In Chichen Itza, El Caracol, the “shell house” (named for its spiral staircase), was a celestial observatory registering constellations and marking the seasons a few hundred meters from the great pyramid, which was marked with deities that vibrated in the sun, and the great ball-court, where winners feasted and losers were fed to the gods.

Scholars of science studies and anthropology have sought to overcome the divide between materials and symbols, objects and subjects—Donna Haraway’s material semiotics, Bruno Latour’s nature-cultures, Andrew Pickering and Karen Barad’s mangled and entwined dances of agency. Ontologies have been explored that do not rely on a divide between humans and other beings—including the perspectival animism ascribed to Amazonian groups by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and the non-naturalist ontologies explored by Philippe Descola. Many contributions to what Descola calls the “anthropology of nature” focus on pre-industrial sites—Amazonian forests and mountains, Aboriginal Australian ancestral rock-formations, and Arctic tundras.7 But cities are the habitat where more than half of the planet’s humans meet the universe. The challenge, then, is to see the modern city as simultaneously material and symbolic; as concrete, sensory, and expressive; as a site of interactions that establish characteristic relations among human dwellers, other living beings, and made and existing objects.

One reason that cities serve so readily as figures of the universe is that they are places people go to learn about the universe. They gather and transmit ideas in monuments, schools, libraries, observatories. Their architectures of districts, buildings, offices, streets, electrical cables, and optic fibers reveal planned and emergent patterns of interaction, collaboration, and information flow.8 In both planned and unplanned ways, cities are cosmograms. One of their most captivating if enigmatic features is the way they embed and choreograph other cosmograms: in temples and cathedrals, in constructions studding the landscape, in encyclopedic museums, in imperial gardens, in constantly updated records and reports. Any given cosmogram engages with other cosmograms, echoing, reinforcing, correcting, subverting, or trying to replace other images of the universe, near or far.

Cosmograms all have a few general characteristics. They are made of particular material elements (paint and canvas, wood, stone, or musical notes and rhythm) in a specific configuration in a particular place. Yet they have specific modes of expression: the ways in which they express the universe, for instance as a list of facts, as a combinatorial set of possibilities, or in an evocative figure. They spell out particular orders of beings and relations: divisions between animal, vegetable, and mineral; natural and supernatural; sacred and mundane. More specifically, they order the social—the stratified and agglomerated association of values among humans—and the earth—what humans depend on to survive—and provide a story: narratives of origin, creation, fall, redemption, return, progress, or decline. Finally, once in place, they undertake actions of various kinds, proposing new orders of being, maintaining or subtly shifting those already in existence, guiding actions, and orienting perspectives.

A city is a world, made of many worlds, intersecting the larger worlds of the universe or pluriverse.9The simultaneous presence of multiple cosmic orders weighs on every city—a pressure of histories, aspirations, conflicting intentions, and tendencies that generates a city’s definitive forms. The multiple and at times divergent cosmograms that are contained within a city—itself a cosmogram—weigh upon each other, accentuating, distorting, critiquing, rendering the others incomplete and at times illegible.

Toward an Urbanism Beyond the Human

A perhaps counter-intuitive starting point for thinking the lived city as a cosmogram is Eduardo Kohn’s How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human.10 Kohn’s ethnography of Amazon life digs into C. S. Peirce’s semiotics as a theory of signification that extends beyond symbols. Signs act and react across species, restlessly shifting across scales and frames of reference. Within this framework, humans appear as just one signifying agent alongside and embedded with palm trees, parakeets, and pumas. Plants, soils, wild animals, and humans associate through representations that are semiotic, but not always linguistic: “one could say tropical plants come to represent something about their soil environments by virtue of their interactions with the herbivores that amplify the differences in soil conditions and thus make these differences important to plants.”11 Rather than present “Amazonian culture” as a system of human symbols imposed upon material, inhuman nature, Kohn explores how those embedded within the “open whole” of the forest think along with it.

Kohn dwells upon wholes of various orders, showing these as constituted and expressed through acts of signification. Accordingly, both human and nonhuman signifying agents are selves, “living thoughts” that “emerge whole” and undergo dynamics of “absence, future, and growth, as well as the ability for confusion.” 12 Selves merge with elements surrounding them and actively pattern future events: “Living thoughts ‘guess’ at and thus create futures to which they then shape themselves.” Selves are “waypoints in the lives of signs—loci of enchantment—and this can help us imagine a different kind of flourishing.” 13

If selves are one level at which signifying elements gather into unified if open wholes, another (borrowing again from Peirce) is that of generals, or form: “Form requires us to rethink what we mean by the ‘real.’ Generals—that is, habits, regularities, potential recurrences, and patterns—are real. But it would be wrong to attribute to generals the kinds of qualities that we associate with the reality of existent objects.”14 Generals and forms have a “possible eventual efficacy,” as patterns, tendencies, and emergent orders within and among existents.15 They are much like the “mind” Gregory Bateson sees arising within systems of self-adjusting loops: “Mind is a necessary, an inevitable function of the appropriate complexity, wherever that complexity occurs.”16 Building on Kohn, might we not consider cities—much like forests—as selves, sites of emergent form, “open wholes,” agents of “living thought?” If so, how do cities think? Cosmograms are the visible trace of a city’s processes of thought.

Cities are havens and engines of signification: sites of complex, coordinated, and spontaneous interaction where multiple and diverse beings (humans, plants, birds, rats, soils, streets, foundations, weathers) undertake recurrent actions of autopoietic self-definition (creating borders, city limits, totalizing representations). The interactions among their components work together in overlapping, robust, and dynamic forms.17 The city is a “living thought” engaged with and remade by multiple beings, at multiple scales and in multiple modes, both within and beyond its membranes and immunological limits. Even as specific cities engage with wider worlds—stretching to the limits of the planet and beyond—they are marked, tinged, and flavored with characteristic, emblematic, even totemic substances: specific products of the earth transformed by human activity and woven into the city’s subsistence. The weight of these accumulated sensations and intersubjective convergences—imaginative and passing impressions, connected with experience—renders the city—any city—as an open-ended, emergent cosmogram.

At the same time, at various points within the city’s moving fabric, humans have made bounded and explicit renderings of cosmic order—deliberate, well-wrought images of the whole. Weighing the city involves both its emergent and explicit modes of expressing totality, including how these modes of cosmic signification overlap in contradictory and opposed, as well as convergent and analogous, ways.

Mauve and Mobile Futures: Chicago, London, Paris

Chicago, London, and Paris are exemplary metropolises of late nineteenth century industrial modernity, where particular patterns of science, technology, and capitalism reorganized human and non-human life in both universal and local ways. Each city gathered and expressed the universe in distinctive material and sensory forms, while their human inhabitants crafted novel images of totality in local idioms.

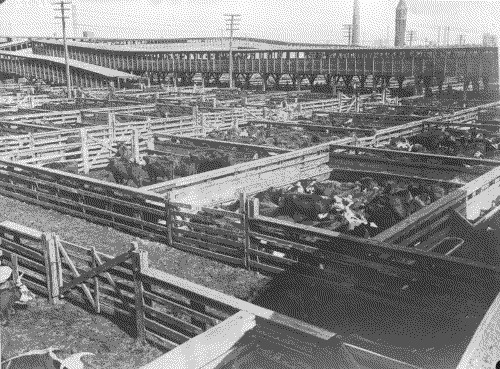

William Cronon’s environmental history of Chicago, Nature’s Metropolis, defines the city at the period of its rapid population expansion in the late nineteenth century not through class politics or its ethnic mix but by the other-than-human entities of corn, cattle, and lumber, as well as the technical processes and forms developed to transform, count, and move them.18 Cronon shows Chicago as a network of flows, a key point in a vast geographical chain held in place by the railroad, which linked a hinterland of productive grid-like fields, pastures, and forests to processing centers and markets on the coast of Lake Michigan.

Fig 2. Chicago Stockyards, 1930. German Federal Archive, Wikicommons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_102-10232,_Chicago,_Schlachtvieh.jpg

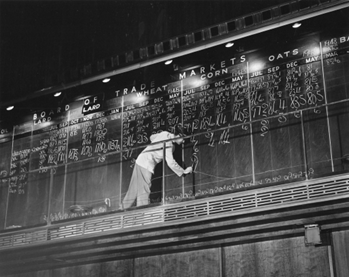

Chicago Board of Trade, 1947. Source: The Chicago Board of Trade Building.

Corn became a standard commodity with assignable value through crossbreeding, mechanized plows, planting machines that lined seeds up in straight and self-similar lines, rows of train cars for shipment, and, most importantly, grain elevators and silos, which combined diverse grains grown under different conditions into a single saleable load. Similar processes transformed cows grazing on the plains into marketable sides of frozen beef—helped by the refrigerated train car—and the great forests of the West into uniformly-sized timber, stacked for maximum capacity on rail beds. Corn, beef, and lumber made the city a palpable reality of taste, touch, and smell, experienced in frame houses, railyards, stockyards, and marketplaces.

The great distance separating the sites of agrarian production in Western Illinois, Iowa, and Nebraska, and the markets in Chicago where grain and meat would be put up for sale brought traders uncertainty: would the price offered today hold for a shipment expected a week later? Was it higher or lower than what the goods could sell for on arrival? Farm agents and buyers thus began exchanging tickets that guaranteed the price of a future delivery; they bought and sold these promised trades according to their estimates—or bets—on their eventual value. This was the first “futures” market, materialized on the slate at Chicago’s Board of Trade.

The living thought of the city—the universe expressed in soils, silos, and steaks—was abstracted and highly condensed in this brand new cosmogram: the quote board making visible the rise and fall of commodities’ values. The new city sutured farmland and market, production and consumption, blending experiences of the plains, trains, and slaughterhouses and detailing them in chalked prices and negotiated future values—new senses and new visualizations that would eventually allow coordination across even greater distances.19

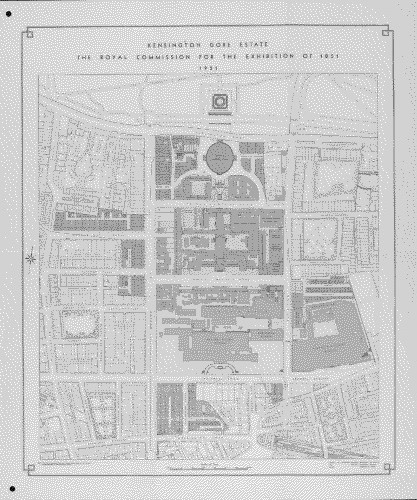

Figure 4. Kensington Gore Estate 1851 (1951). Source: https://www.dsdha.co.uk/research/57a460ee0f1f9b0003000001/Re-imagining-the-Albertopolis

Figure 5. Prince Albert Memorial and Royal Albert Hall. Source: ChrisO/Wikimedia Commons.

London was always a complicated cosmos, with canals and rails and markets heaving with colonial cotton, tea, and sugar. In the late nineteenth century, the city developed the district of South Kensington, beneath Hyde Park and a stone’s throw from Buckingham Palace, making permanent the displays of the Great Exhibition of 1851.The district was nicknamed “Albertopolis,” for Queen Victoria’s consort, who helped with its planning.

This was a city within a city. We might be tempted to see it growing from the top down, from the squat cylinder of the Royal Albert Hall married to the Albert Memorial, an Italianate shrine for the dead prince. This finely-crafted symbol deliberately condenses the cosmos: its eight corners show the world’s regions and peoples along with its useful arts, engineering and agriculture; its top represents the virtues, tapering steeply to a crown of angels and a cross.

This intense symbolic effort to capture the essential domains of empire and universe echoes in more diffuse and telling ways to the south, along Exhibition Road. In the laboratories of what is now Imperial College—formerly the Normal School for Science, modeled on the centralized French Grandes Ecoles—Joseph Perkins transformed the industrial byproduct of coal tar into the purple dye of mauveine, spurring a revolution in Victorian mourning style and industrial research into chemical products and processes. The Natural History Museum’s ornate entrance hall long held a replica of Pittsburgh’s long-necked dinosaur skeleton, Dippy, the Diplodocus carnegii named for the oil tycoon Andrew Carnegie whose petroleum expeditions unearthed ancient remains.20 The museum’s collections (lastingly placed into order by the idealist anatomist Robert Owen) map the kingdoms, classes, and transcendent forms of all living things. Deeper time unfolds in the Museum of Geology, opened in 1935 on the foundation of the rocks collected for the Museum of Economic Geology, its specimens gathered in the wake of new railroads, canals, and the hunt for coal.

Further south, the original mission of the Victoria and Albert Museum was set by the Department of Science and Art to display and transmit methods for practical and technical modification of matter: industrial products like textiles, metals, and food, and the processes behind them. The natural sciences broke away in 1900 with the opening of the Science Museum, in a moment defined by H.G. Wells as one of “petrol and progress.” 21 Recent protests forced the Science Museum to abandon one of its long-term supporters—Equinor, a Norwegian oil giant—but British Petroleum and other fossil fuel corporations remain key funders.

Albertopolis was Carbonopolis: a pleasant and informative destination for school children and tourists, teaching lessons of identification, extraction, and control of things and people from one end of the globe to the other—powered, paid for, and polluted by fossil fuels.22 This central fact is only dimly legible in the monument to Albert’s global reign.

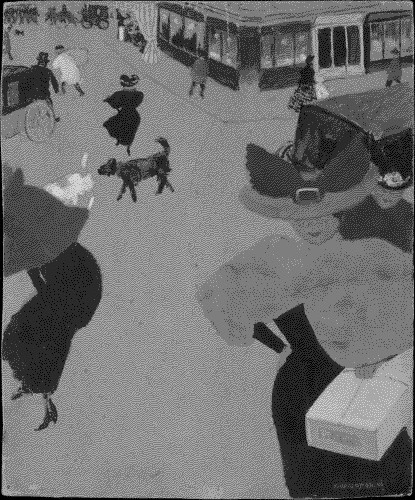

Figure 6. Félix Vallotton, Coin de Rue à Paris, 1895.

Figure 7, Félix Vallotton, Au Bon Marché, 1898.

Nineteenth-century Paris was a patterning of substances, senses, and moving lines. Its interconnected sites reveal a distinctive style for joining idea and matter via sensory technologies—what the physicist-philosopher André-Marie Ampère called la Technaesthétique.23 The dye works at the Gobelins manufactory tinted tapestries and fashions, while the theory of contrasting colors by its chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul fed into painting and industrial sense-production in the form of perfume, foods, and clothing. All these sensory objects were arrayed and sampled throughout the city, creating novel experiences of consumption both public and intimate, captured in their irony and dynamism in Félix Vallotton’s Scenes of the Paris Streets (1893).24

At the same time, Paris also hosted laboratories to track perception and graphically trace the rhythmic forms of nature. Engineers of the Ecole Polytechnique and Ponts et Chaussées traced routes, canals, and the path of steam with increasingly efficient engines, railroads, and electric lines; these fluid contours curled into the art nouveau ornaments of the Metro. Their vanishing lines dissolved landscapes into patches of color, while poets dissolved language into units of sound and meaning: an electric forest of symbols.25

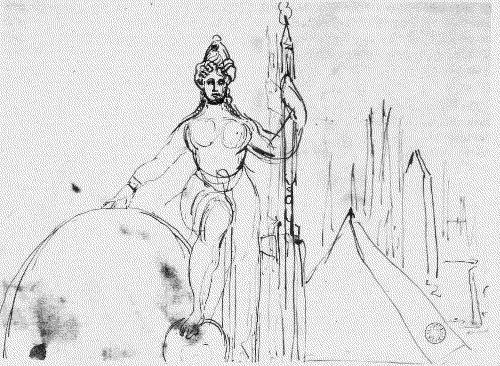

Already in the 1830s, the Saint-Simonian engineer Charles Duveyrier plotted out “La Ville Nouvelle,” redrawing the city in the form of a man. Its districts were rationally apportioned: science on the left, shops and industry on the right, visible in “the parabolic curves of the foundries and forges, the blackened cones of the furnaces.” Between the legs were “buildings consecrated to the ecstasies of the mind and the delirium of the senses,” theaters and opera houses extending down the Champs-Elysées to the Place de l’Etoile. The head was superimposed on the Ile de la Cité, where Notre Dame would be replaced by a gigantic, illuminated “woman-temple” styled to recapitulate “all the religions of the past”: “the Kremlin, mosques of the Arabs, pagodas of India and Japan.”26

The Saint-Simonian “Woman-Temple,” c. 1829. Source: Album Machereau, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, BNF.

Though the Temple-Femme was never realized in Paris, it was an inspiration for New York’s Statue of Liberty. The Saint-Simonians’ sublime urban natures guided Baron Haussmann’s transformation of Paris into the opulent city of broad boulevards, glittering shops, and constant spectacle. Industry largely moved to the periphery with the runoff from weaving, dyeing, and leather processing flowing into the Seine. But even the sewers and catacombs became tourist attractions in the city of profane illuminations, made possible by heavy and constantly renewed investments in infrastructures of circulation.27 Monuments and tourist sites, endlessly photographed and reproduced, evoke the worlds of sensuous order channeled through Paris’s passages and streets.

Synecdoche: New York, et al.

These cities, or cities within cities, actively signify all the way through. Material entities—trees, air, water, and wildlife, along with coal, lumber, iron, glass, and steel—demonstrate their capacities in taut and elastic interaction with others. Humans stir patterns of order in their midst, counting, commemorating, painting, packaging. Each city, considered as an emergent cosmogram, is also summarized by the deliberate cosmograms within it: the Board of Trade’s pit and quote board, the Albert Memorial, the Temple-Femme. These concentrated, deliberate figurations of totality—each of which was given a national accent but stands in for the universe as a whole—involve what Kohn calls as an “upframing”: a shift of perspective from particular entities and their actions to more general patterns.28

The rapid triangulation of these three world cities calls for further upframing, such as by considering how these emblematic figurations of the city-as-cosmos commune with other visible and hidden parts of the metropolis, how each city receives and responds to much broader regions, and how each composes itself with other cities, with the rest of the planet, and with the universe stretched even more widely. Not coincidentally, these three cites hosted World’s Fairs between 1850 and 1900, making each of them even more explicitly a city of the world, holding other nations, their products, and their populations in miniature.

Today it’s even more clear that no city—or forest—stands alone.29 We each live in one place but the others are here, as images and words, as products and wastes, as embodied emissaries, as near and distant rumbles, threats, and pleas sent through light-speed communications. We navigate topological entwinements of images, signs, and forces, ebbs and flows of numbers, feelings, materials. Each locus draws and weighs on others. Though impossible to measure completely, this pluriverse of habitations presses down upon us, demanding new perspectives and protocols to tally, frame, and expose it—to trace its tangles, to draw new and more livable forms.

Footnotes

- Gregory Allen Schrempp, Magical Arrows: The Maori, the Greeks, and the Folklore of the Universe (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992); Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science” in A Universal History of Infamy, trans. Norman Thomas de Giovanni (Penguin Books, 1975).

- Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st Century Economist. (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018).

- Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World: Lowell Lectures 1925 (New American Library, 1925).

- John Tresch, Cosmograms: How To Do Things with Worlds (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming); John Tresch, “Cosmic Terrains (Of the Sun King, Son of Heaven, and Sovereign of the Seas),” e-flux journal #114 (December 2020).

- Jacob Olupona, City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination (University of California Press, 2011); Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: The Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press 1988).

- A debate exists over whether cities in Mesoamerica were cosmograms, or whether this reading was just a projection by conquistadors, inspired by Dante and imaginaries of Rome, to find a concentric and hierarchical cosmos. Michael E. Smith, "Did the Maya build architectural cosmograms?," Latin American Antiquity 16, no. 2 (2005): 217-224.

- See Philippe Descola and Gísli Pálsson, eds. Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives. (Taylor & Francis, 1996.)

- David N. Livingstone, Putting science in its place: Geographies of scientific knowledge (University of Chicago Press, 2019); Thomas Gieryn, "City as truth-spot: Laboratories and field-sites in urban studies," Social Studies of Science 36, no. 1 (2006): 5-38.

- Marisol De la Cadena, and Mario Blaser, eds. A World of Many Worlds (Duke University Press, 2018).

- Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2013). Kohn’s title riffs on Marshall Sahlins’s How “Natives” Think: About Captain Cook, for Instance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), which in turn plays on Lucien Lévy-Bruhl’s disparaged theories of “mystical participation” in How Natives Think (New York: Knopf, 1925) and the translation by Lilian Clare, “La mentalité primitive.” In a new French edition Frederic Keck reframes Lévy-Bruhl’s emphasis on “participation” as a reflection how people “act under the impact of forces that are imperceptible to the senses but nevertheless real”; Frederic Keck, introduction to La Mentalité Primitive by Lucien Lévy-Bruhl (Paris: Flammarion, 2010).

- Kohn, How Forests Think, 82.

- Kohn, How Forests Think, 92

- Kohn, How Forests Think, 90

- Kohn, How Forests Think, 186.

- Kohn, How Forests Think, 186.

- Gregory Bateson “Pathologies of Epistemology” (1969), in Steps to an Ecology of Mind (New York: Ballantine, 1972), 490. Kohn’s frequent reference to Bateson highlights the compatibility and continuity between Peirce’s semiotic and Bateson’s cybernetic metaphysics. See also Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan, Code: From Information Theory to French Theory (Duke University Press, 2022).

- Bruno Latour and Emilie Hermant, Paris, Ville Invisible (Paris: Les empecheurs de penser en rond, 1998).

- William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W.W. Norton, 1991).

- Cristóbal Amunátegui, "Order for Profit: On the Architecture of a Nineteenth-Century French Agency," Grey Room 95 (2024): 6-41; Caitlin Zaloom, Out of the Pits: Traders and Technology from Chicago to London (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006); Joseph Vogl and Christopher Reid, “Taming Time: Media of Financialization,” Grey Room 46 (2012): 72-83.

- Lukas Rieppel, Assembling the Dinosaur: Fossil Hunters,Tycoons, and the Making of a Spectacle (Harvard University Press, 2019).

- Quoted in Robert Bud, "Infected by the Bacillus of Science: The explosion of South Kensington" in Science for the Nation: Perspectives on the History of the Science Museum, ed. Peter Morris (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2010), 12.

- Thanks to Simon Schaffer and Caitlin Doherty for their conversation about Carbonopolis in Somers Town, 2022, and to Charlie and Catherina Gere for cosmic readings of the Albert Memorial.

- John Tresch, “La ‘technesthétique’: répétition, habitude et dispositif technique dans les arts romantiques,” Romantisme 150, no. 4 (2010): 63-73.

- Éloi Rousseau and Johann Protais, Les plus belles oeuvres de Vallotton (Paris: Éditions Larousse, 2013), 44. On the dynamic fusion of sense and calculable line, see Robert Michael Brain, The Pulse of Modernism: Physiological Aesthetics in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015); and Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism (Cambridge, MA: Zone Books, 2024).

- Timothy J. Clark, The painting of modern life: Paris in the art of Manet and his followers (Princeton University Press, 2015); Susan Buck-Morss, The dialectics of seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (MIT Press, 1991).

- Charles Duveyrier, “La Ville Nouvelle,” in John Tresch, The Romantic Machine: Utopian Science and Technology After Napoleon (University of Chicago Press, 2012), 192-194, 218-219; Antoine Picon, Les Saint-simoniens: Raison, imaginaire et utopie (Paris: Editions Belin, 2002).

- Mark Wigley, "Network Fever," Grey Room 4 (2001): 82-122; Brain, The Pulse of Modernism.

- Kohn, How Forests Think, 178.

- Anna Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

John Tresch

John Tresch is Mellon Chair and Professor of History of Art, Science, and Folk Practice at the Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Study, University of London. John Tresch’s research examines changing methods, instruments, and institutions in the sciences, arts, and media from the early modern period to the present, as well as connections among disciplines, practices, and cosmology. He has published two books on 19th century sciences and their connections to technology, arts, literature, and politics. From 2005-2018 he taught History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; he has held fellowships at the New York Public Library, the Institute for Advanced Studies, and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, and has been visiting researcher at King's College London and the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales.